Posted on 04/10/2017 by David

Have you ever wondered what secrets the sea that surrounds us holds? Lurking in the inky deep lie the wrecks of many historic tragedies that claimed lives, cut short maiden voyages of impressive new technologies and that have indelibly changed our seabed.

Many ships have been lost in the waters surrounding North Wales, but these are some of the most compelling tales. Just think - you may well have passed these sites before and never knew what lay below the ocean surface!

HMS Conway, Menai Strait

In the 1850s, new laws required merchant navy officers to be better trained, and therefore more training school ships were built. The first of these was HMS Conway which had her maiden voyage in 1859.

She was moored at Rock Ferry on the Mersey but because Liverpool was a target for devastating Luftwaffe air raids during WW2, it was decided the Conway should be relocated to the relative safety of the Menai Strait.

In 1953, the ship needed to be refitted. The captain, Eric Hewitt, argued that three tugs were needed to tow her to Birkenhead, but a management committee insisted only two were to be used.

An unexpectedly strong current meant the ship was making very little progress. As a result, the rear tug was moved to the front of the ship in an effort to generate extra power. With the rear left uncontrolled in bad weather, the Conway ran aground minutes later.

Beached on flat rocks (known as the Platters) near Menai Bridge the ship was stuck fast; then when the tide retreated, her back broke and she was declared a wreck.

The wreckage of the Conway remained in the Menai Strait until 1956, when work began to remove her. In another unfortunate twist, the ship caught fire during dismantling and was burned down to water level, where her remains can still be seen at very low tide today.

Resurgam, Rhyl

The Resurgam (a Latin phrase meaning 'I shall rise again') was the name given to two cutting-edge Victorian submarines, designed as weapons to penetrate the chain netting on the hull of ships which deflected attacks by torpedo vessels.

The first Resurgam was a prototype vessel that never saw combat and the second sank on her maiden voyage off the coast of Rhyl in 1880. She was presumed lost for 115 years but was rediscovered in 1995, fifty feet under water.

Resurgam II was bound for Portsmouth where it was to give a display to the Royal Navy. During the journey, mechanical problems forced it dock in Rhyl’s Foryd Harbour for repairs.

The crew departed Rhyl in bad weather on the 24th of February with the Resurgam towed by a steam yacht called Elphin, but this subsequently developed engine problems. The crew of the submarine boarded the yacht to help but because Resurgam's entry hatch could only be closed from the inside the submarine began to take on water and flood.

The tow-rope snapped under the weight of the water and the Resurgam sank into Liverpool Bay, never to be seen again.

In 1995, the missing submarine was discovered by experienced wreck diver, Keith Hurley, as he attempted to clear snagged fishing nets. It is a designated protected wreck but parts of the steering tower and many removable items have long since been stolen away by greedy wreck hunters.

Pwll Fanog, Menai Strait

In 1976, the remains of a medieval cargo ship known as a ballinger were discovered. The boat - a small, fast ocean going vessel constructed almost entirely of wood - was found 11m under the water in the Menai Strait near Caernarfon.

It is believed the ship was built in mid-15th century, during the Wars of the Roses, and sank at Pwll Fanog around 1530.

Ballingers were a common site on the Welsh coast, having been introduced by the English during the Welsh conquest of the 13th century. They were useful boats for carrying small loads and transporting people and supplies over short distances.

Historian's believe the Pwll Fanog ship was bound for Beaumaris Castle. Why? It was carrying a cargo of 40,000 neatly stacked slates and Beaumaris was the centre for slate export from North Wales at the time. It is likely that the ship sank while at anchor, waiting for the tide to turn so she could sail with the current to port.

The wreck at Pwll Fanog is the oldest slate-carrying wreck to have been discovered.

HMS Thetis, Llandudno

The story of the Thetis is a tragic one, with the wreck referred to as the 'worst ever submarine disaster' when she became the final resting place for ninety-nine crew in 1939.

Built by Cammell Laird in Birkenhead, HMS Thetis was launched in June, 1938. She left Birkenhead for Liverpool Bay under Lieutenant Commander Guy Bolus to conduct final diving trials, accompanied by the tug, Grebecock, and carrying a crew of 103.

On her first dive attempt, Thetis struggled to gain depth. An officer opened the torpedo tubes to allow water in to add weight to the vessel but a blocked tube stopped the water flowing out again. In the ensuing confusion the torpedo tubes were opened from the inside and seawater rushed into the submarine. The deluge forced the bow of the submarine down and it sank 46m to the seabed.

The ship was just 12 miles off the Great Orme when it sank. A rescue mission was launched by the Royal Navy from Portsmouth by the nearest rescue ship was hundreds of miles away.

The crew acted quickly to dump excess water and fuel, allowing the Thetis to rise stern-first above the waterline. But as the hours ticked by, the crew of the Grebecock became increasingly concerned for the safety of those onboard the Thetis.

A handful of men escaped with their lives but, tragically, rescue for the rest came too late. A salvage ship failed to raise the Thetis from the seabed and, indeed, worsened the situation when a steel cable snapped and sent the submarine plummeting to the seabed. Carbon dioxide poisoning slowly suffocated the crew and all were lost.

One witness said: “I remember watching footage of rescuers who could hear banging coming from inside and were banging back to let those trapped inside know that they were there."

It would be another 4 months until the wreck of the Thetis could be retrieved by a salvage ship and the corpses laid to rest with full naval honours.

In Thetis Down: the Slow Death of a Submarine, historian Tony Booth revealed that rescuers could have saved the entire crew in just 5 minutes by cutting air holes in the steel hull.

Buying time, a larger hole could have been cut to release them, but the move was refused by the Admiralty. They believed that with the Second World War looming saving the submarine was more important than saving the crew.

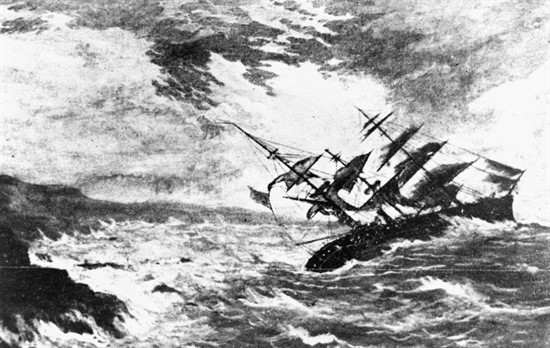

Royal Charter, Moelfre

The coast of Anglesey is regularly ravaged by storms from the Irish Sea but on the night of the 25th of October 1859, an exceptional squall mauled the island with tragic consequences. It was named the single worst storm of the 19th century.

The steam clipper Royal Charter was making her way to Liverpool from Australia with around 375 passengers, 112 crew and £300,000 worth of gold (estimated at around £77 million in today's money) on board. With no modern technology to warn them, the crew were unaware of a hurricane bearing down on them as they rounded the tip of Anglesey.

As the winds strengthened, all attempts to steer the ship manually by her rudder failed and, drifting dangerously close to the rocky Anglesey coastline, the Royal Charter put out a distress call. Unfortunately, owing to the ferocity of the storm, no ship could come to their aid.

When the captain ordered the anchors dropped the anchor cables snapped under the strain of the storm. In desperation, orders were given for the masts and rigging to be cut down to give the clipper a fighting chance steam against the gales. Too late, Royal Charter was driven onto a sand bank.

Crewmen and locals instigated a rescue effort but the tide started to rise, lifting the ship off the sandbank. Waves threw the ship onto nearby rocks, breaking it in two. Those who did not drown were battered to death on the rocks, and only around 40 of almost 500 onboard survived - every woman and child was killed.

Over the next few weeks, bodies and gold were recovered. Many of the dead were buried in nearby Llanallgo Church but the gold found its way into people's pockets, despite the authorities best efforts to collect it.

Reverend Stephen Roose Hughes of Llanallgo took it upon himself to inter the dead, writing hundreds of comforting letters to their relatives. The tragedy took a terrible toll on him, and he died within three years, aged just forty-seven. His body rests in the churchyard with them.

To this very day, daring divers and greedy treasure seekers continue to explore the wreck off the coast near Moelfre in the hope of striking it lucky.

Images courtesy: HMS Conway, Alfie Windsor 2004. Resurgam replica, © Copyright Chris Allen and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence. A boat similar to the ballinger found at Pwll Fanog, VollwertBIT 1991, via Wikimedia Commons. HMS Thunderbolt formerly HMS Thetis, Imperial War Museum. Royal Charter, University of Queensland.